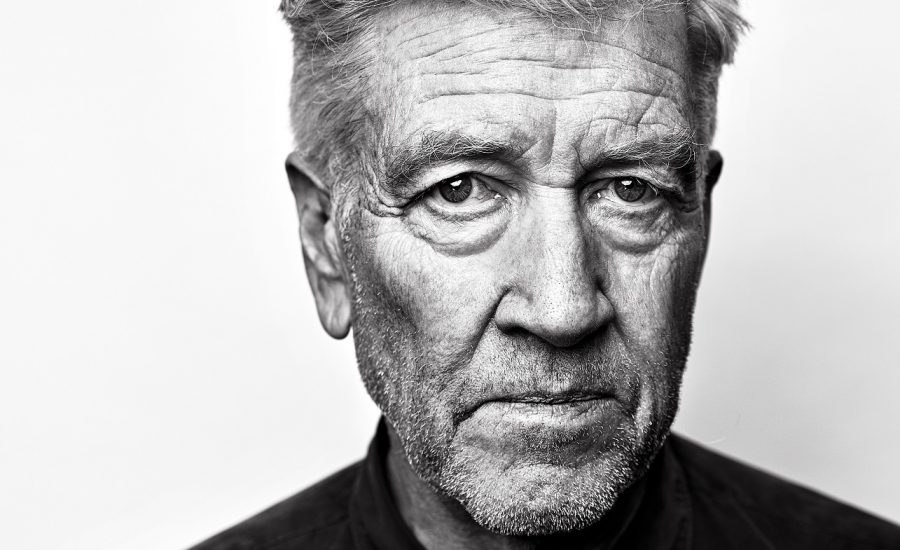

Photo Credit: Josh Telles

The works of late David Lynch are full of ambiguities that derive from his habitual distortion of time; inversion of characters; and creation of ironic, dreamlike worlds that are mired in postmodern irony and crisis. Granted, he’s not the first to have broken ground with his vision of audiovisual storytelling – yet Lynch has somehow managed to go even more leftward with his own, very “Lynchian” approach. Audiences and critics alike have long been equally enchanted and baffled by his brooding, oftentimes kitsch but ultimately very earnest images of the human condition. But what is so special about his trade that separated him from, pretty much, everyone else?

The answer arguably lies in the unique way he manipulated expectations. Lynch looked for “feel” which in itself informs a story first; and based on that piece of information, the technique used would cater for that particular story. As he famously reiterated in almost any interviewing panel he’d taken part in, “ideas dictate everything – they come along and they string themselves together, and they form a whole.” While many directors see a soundtrack as merely a supporting element – enhancing performances, dialogue, or setting a mood – Lynch recognised that sound was just as crucial as, if not more than, the visuals. Beyond shaping the audience’s visual experience, he also understood how deeply music could affect his characters, who often seemed mesmerised and haunted by the melodies within their own stories – meaning Lynch also redefined how audiences “hear” films. With that, to grasp the distinctive strangeness of his works, one must pay close attention to the music – or absence of it.

Lynch’s idiosyncratic use of sound design can be traced back to his first “moving painting,” 1967’s Six Men Getting Sick which he made as a fine art student at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. In this piece, a siren was used to accompany a one-minute film loop of animated visuals which were projected onto a specially designed sculpture-screen. Lynch has often reiterated that the idea behind this project came to him while working on a painting of a woman in a garden at night. “I was sitting, looking at this painting. And from that painting, I heard a wind, and then I saw the green start to move.” Dean Hurley, Lynch’s last supervising sound editor and long-time employee noted however that “[…] in the telling of that story, people skip over the wind part and jump to the painting started to move.” Indeed, people tend to read Lynch purely as a director, when he himself identified as a sound man.

His early forays into film sound were carried out as early as 1977, when Lynch released his debut feature-length, Eraserhead. The infamous indie nightmare turned heads for its jarring visual language, and saw him team up with an equally eccentric sound designer, the late Alan Splet. For over a year, they experimented with unconventional folly techniques to evoke a specific “reaction as feel.” By layering static hisses, distorted gurgles, and eerie metallic clangs, the film’s world takes on a life of its own, becoming just as significant as the characters within it. Here, music and sound design aren’t merely supporting elements – they propel the narrative forward, delving into unexplored depths of both the characters’ psyches and the audience’s subconscious.

Lynch also wrote the lyrics for In Heaven (Lady in the Radiator Song), performed by Peter Ivers on the film’s soundtrack. Most interestingly, the Lady in the Radiator character wasn’t part of the original script – the idea fully took shape when Lynch noticed a radiator on set that resembled a small stage. Though Lynch’s films are often attributed to surreal readings, they would frequently emerge from the ordinary, elevating everyday moments into something profound. As he once put it, allowing the subconscious to guide a project’s direction is part of embracing life’s unpredictability: “The world is filled with beautiful accidents.” In Heaven later developed a cult following, inspiring covers by artists like the Pixies, Bauhaus, and Devo. Both moments signalled the start of Lynch’s distinctive approach to sound design, where he instinctively deconstructed pop music to heighten tension and mystery, thus making it a central force in his storytelling.

Splet remained a faithful Lynchian name-stay through 1980’s biographical drama The Elephant Man, 1984’s big-studio sci-fi adventure Dune, and the pre-production in 1986’s neo-noir mystery Blue Velvet. It was at that time when Lynch teamed up with late composer, Angelo Badalamenti who not only contributed to the film’s score but also appeared on-screen as a pianist, accompanying Isabella Rossellini’s haunting performance of the Roy Orbison classic. Widely regarded as one of the most singular creative relationships in the film world, the duo also released a free-jazz album in 2018 under the joint moniker, Thought Gang. This short-lived project had originally died out by the mid-90’s, yet several previously recorded pieces were included across Lynch’s films. More than just collaborators, the pair formed a lifelong friendship that permeated through their work together. “He was a genius,” Lynch said of Badalmenti who passed in 2022, “I miss him like crazy.”

Perhaps their most enduring musical achievement, however, was the iconic Twin Peaks theme – co-created with screenwriter/producer Mark Frost, the series revolutionised cable entertainment and marked a turning point in television drama with its uncanny tone and almost musical pace. As Lynch told Pitchfork in 2016: “The music of ‘Twin Peaks’ was integral to the experience … So much came out of the music that made the mood and the place and the feeling of the show come to life.” The Badalamenti leitmotif rolls up with every opening sequence, whereas its full-band version, Falling, featured the melancholic prowess of late singer Julee Cruise – the trio had previously crafted Mysteries of Love for the Blue Velvet’s unexpectedly uplifting ending, which led to 1989’s dream-pop classic, Floating into the Night LP. Cruise’s haunting, reverberated vocals came to symbolise the voices of Lynch’s troubled female characters, which in itself came to be an indispensable element in Lynch’s creative repertoire – be it in film or sound. “I was a belter, and he turned my voice around to create that angelic sound,” Cruise recalled in 2005 of working with Lynch and Badalamenti.

It is apparent at this point that collaboration was central to Lynch’s career, but unlike many of his contemporaries, Lynch relied on an action-and-reaction response from his peers – almost tapping into their subconscious rather than asking them to reproduce his own self-imposed vision onto them. Nine Inch Nails frontman Trent Reznor, who first worked with Lynch on 1997’s paranoid neo-noir Lost Highway, had this to say about him at a promotional interview with Rolling Stone magazine: “He’d describe a scene and say, ‘Here’s what I want. Now, there’s a police car chasing Fred down the highway, and I want you to picture this: There’s a box, OK? And in this box there’s snakes coming out; snakes whizzing past your face … And he hadn’t brought any footage with him. He says, ‘OK, OK, go ahead. Give me that sound.’” Despite explaining that he didn’t typically work that way, Reznor agreed to take on the project. Most notably, Lost Highway featured prominent 90’s alternative artists; from David Bowie and The Smashing Pumpkins who also contributed an original song, to Henry Rollins and Marilyn Manson who appeared on screen. Tied together with Barry Adamson’s sleek, almost cartoonish jazz score, the resulting film’s soundtrack created a fusion of retro influences and modern alternative rock, mirroring Lost Highway‘s high-tech, voyeuristic take on film noir.

Beyond filmmaking, Lynch shared his directorial duties for many music videos, including Rammstein (Rammstein), Chris Isaak (Wicked Game), and Nine Inch Nails (Came Back Haunted). In 1998, Lynch released his first collaborative studio album, Lux Vivens, with Jocelyn Montgomery. The album was engineered by John Neff, with whom Lynch later collaborated on BlueBOB in 2001. Described as an industrial blues album, it showcases music co-written by the duo, with Lynch providing the lyrics and Neff serving as the lead vocalist. Some of Lynch’s found lyrics would date back two decades prior, and explore themes of paranoia and noir fiction. The album blends elements of rock and roll, surf, and heavy metal, leading critics to draw comparisons to artists like Tom Waits, Captain Beefheart, and Link Wray. In 2007, Lynch put out a series of recordings, including the soundtracks for his final film, 2006’s Inland Empire and his 2007 retrospective exhibition The Air Is on Fire respectively; the collaborative album Polish Night Music with Marek Zebrowski; and his debut solo single, Ghost of Love.

He went on to release two full-length albums as a solo artist, 2011’s Crazy Clown Time and 2013’s The Big Dream respectively – both atmospheric, blues-influenced works that included collaborations with artists such as Karen O., and Lykke Li. This was followed by a remix EP for The Big Dream which saw Lynch embracing the remix culture and reworking tracks by Moby, Mylène Farmer, and Agnes Obel. Unsurprisingly, Lynch’s influence on alternative music extends far beyond direct collaborations. Goldfrapp’s 2013 Tales of Us was inspired by his style, and Flying Lotus featured Lynch’s voice on Fire is Coming. Experimental outlet Xiu Xiu released the 2016 tribute album, Plays the Music of Twin Peaks following the Lynch/Frost announcement they would bring back Twin Peaks for a limited series, while indie acts like Mount Eerie and Sky Ferreira have publicly expressed their admiration.

Over the years, Lynch contributed as a guest musician, producer, and remixer on various projects, including 2010’s Dark Night of the Soul by Danger Mouse and Sparklehorse, as well as multiple dream-pop recordings with Chrystabell – herself also appearing in the Twin Peaks cinematic roster as Agent Tamara Preston. Their most recent collaborative project, 2024’s Cellophane Memories was inspired by a flash of red light Lynch once saw in the trees during a walk. Lyrically, Cellophane Memories echoed themes that defined Lynch’s films – dark forests, moonlit kisses, small-town nostalgia, and haunting nightmares; all woven together into an evocative sonic collage of archival recordings from Lynch, Hurley, and Badalamenti. What proved to be Lynch’s final project can now be seen as a beautiful homage to an artistic life and journey that, as longtime collaborator and close friend Kyle MacLachlan said at the 2025 Writers Guild Awards, “tested the limits of what we were capable of.” Yet, despite his musical intuition, Lynch never considered himself a true musician. “I’m not really a singer, but my voice is treated like any other instrument – you can tweak and manipulate it in so many ways these days,” he told The Guardian in 2010. Though he felt comfortable in the studio, he was hesitant about recording and avoided live performances. As for singing in the shower? “I don’t shower too often,” he quipped.

To that end, understanding how Lynch’s unique timbre ebbs and flows within the all-encompassing field of recorded sound, unlocks the indelible significance of his work in film and sound alike. As film scholar Michel Chion once put it: “Lynch can be said to have renewed the cinema by way of sound … [In relation to film] Sound has a precise function, propelling us through the film, giving us a sense of being inside it, wrapped within its timespan.” What this suggests is that the spectator is not only enclosed within the film’s temporality, but is simultaneously wrapped within the folds of each filmic soundscape. This is an apparent observation that helps us peer into Lynch’s artistic intent, and what he tried to achieve through sound – movement is mirrored by sounds, thus allowing Lynch to construct especially powerful relationships between music and fantasy through his works. In a Blu-ray interview for 2001’s lauded Mulholland Dr., Lynch underlined how sound would often shape his visuals, explaining that, “a lot of times, sound dictates picture – you find a piece of music, and a scene pops out of this music.” A key example of this motto can be found at the hinge of the film, in the Club Silencio scene.

Here, the two lead female characters, Betty and Rita visit a secluded club where an eerie magician declares in multiple languages that “there is no band,” and that all the music performed there is just a recording. He then gestures to a trumpeter, who appears to play live but separates his hands while the sound continues – proving the illusion. As thunder-like sounds echo, Betty trembles involuntarily before the magician vanishes in blue smoke. Then, singer Rebekah Del Rio, introduced as La Llorona de Los Angeles, takes the stage and performs a Spanish version of Roy Orbison’s hit single, Crying. Her acappella performance deeply moves Betty and Rita, bringing them to tears – until she suddenly collapses, yet her voice keeps playing, reinforcing the illusion.

Though the audience has been warned that “this isn’t real,” the performance remains emotionally powerful. Lynch’s approach to sound here plays with schizophonia – the separation of sound from its original source. Audiences expect sound to come from a visible source, but Lynch subverts this expectation by “removing the band.” This disconnect creates unease, affecting both the characters and viewers. Narratively, the song Crying reflects Lynch’s recurring theme of lost or fallen women, where tears become a language of their own – expressing grief and longing beyond words. In the end, the film leaves us uncertain about what is real or an illusion, awake or dreaming – immersed in a haunting world where all we can do is cry, and in true Lynchian fashion, music is at the crux of it all. The scene’s unsettling yet hypnotic energy made the real-life opening of Club Silencio in Paris in 2011 a much-anticipated event. Designed by Lynch himself, the venue mirrors the film’s dreamlike aesthetic with red velvet curtains, gold-adorned tunnels, and ambient lighting. Reflecting on the space, Lynch remarked on its grand opening: “Looking at what we have done, I feel myself almost immortal – I have the feeling that I have coaxed out some of the atmosphere and the characters from my films, and even from my music.”

Elusively cryptic with his outward imagery, and notoriously vague in his interviews, Lynch was adamant that an intelligent audience already knows the answers they are looking for; but they do not trust their intuition, and want to have someone else tell them: “I always say that cinema is sound and picture, flowing together in time,” Lynch has famously reiterated. “When all the elements come together, you can get this thing where the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.” Decades later, debates regarding the potential meanings and interpretations of his works still circulate. But maybe, instead of focusing on the tree, the answer lies somewhere in the forest – we are just not sure where exactly. If we pay attention to the sounds, we might eventually hear a band.

David Keith Lynch (20th January, 1946 – 15th January, 2025)